← Archive home

Daniel Robbins, Senior Curator of Leighton House, discusses the culmination of the restoration of Leighton House and explains how it marks a truly transformational moment in the museum’s long history.

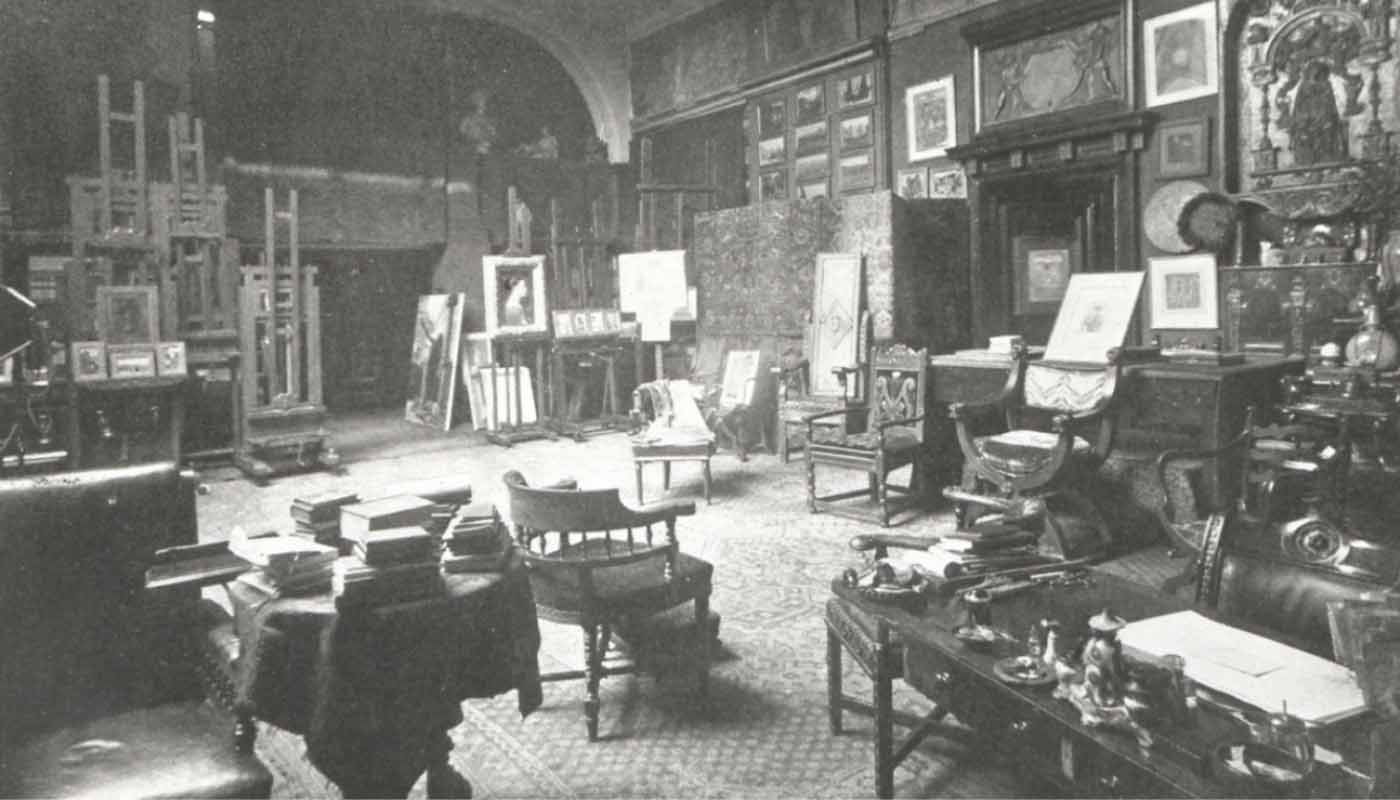

When Lord Leighton died in 1896, he left in his wake a house and collection of great significance. Leighton House, the Victorian ‘Studio House’ designed by Leighton with his architect George Aitchison, was complete with tiles from the Middle-East, gold mosaic friezes and opulent decoration, in combination with the more prosaic spaces for living and working. For more than a century, it has been a museum of extraordinary interiors with artwork by Leighton and his contemporaries that made up the Holland Park Circle. Now owned and operated by the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea, it has undergone an £8 million renovation and expansion that completes the evolution of the house. Filled with flamboyant interiors, including the spectacular Arab Hall, now complemented by the new helical stair with artwork by Shahrzad Ghaffari entitled ‘Oneness’, the house is poised to realise the ambition of becoming a ‘Hidden Gem to National Treasure.’

The shortlisting of Leighton House for the Art Fund Museum of the Year 2023 comes seven months after reopening to the public. This nomination, as part of the world’s largest annual museum prize, is the ultimate recognition of a project that has transformed virtually every aspect of the museum and its operation.

The remarkable house that Leighton created has always had the capacity to surprise and captivate visitors since it first became a museum around 1900. Between 2008–10, the restoration of the historic interiors re-established Leighton’s rich decorative schemes, eroded over the course of the twentieth century. Ceilings were re-gilded, floorboards re-painted and additional objects and furnishings reinstated. But the success of this project could not mask the multiple shortcomings that remained in the operation of the museum as a whole; a lack of space and facilities that compromised the visitor experience, the care of the collections and the fabric of the building itself.

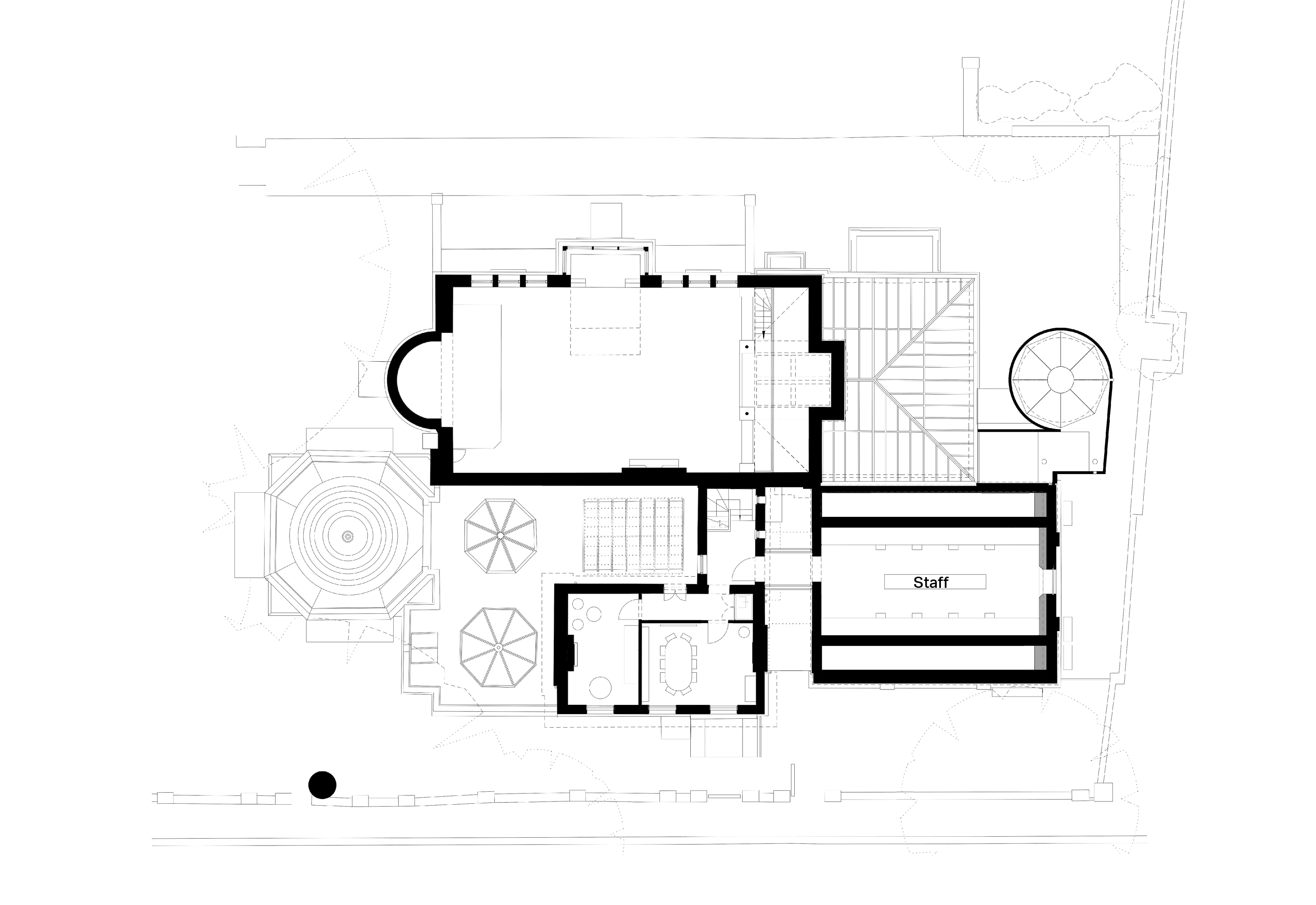

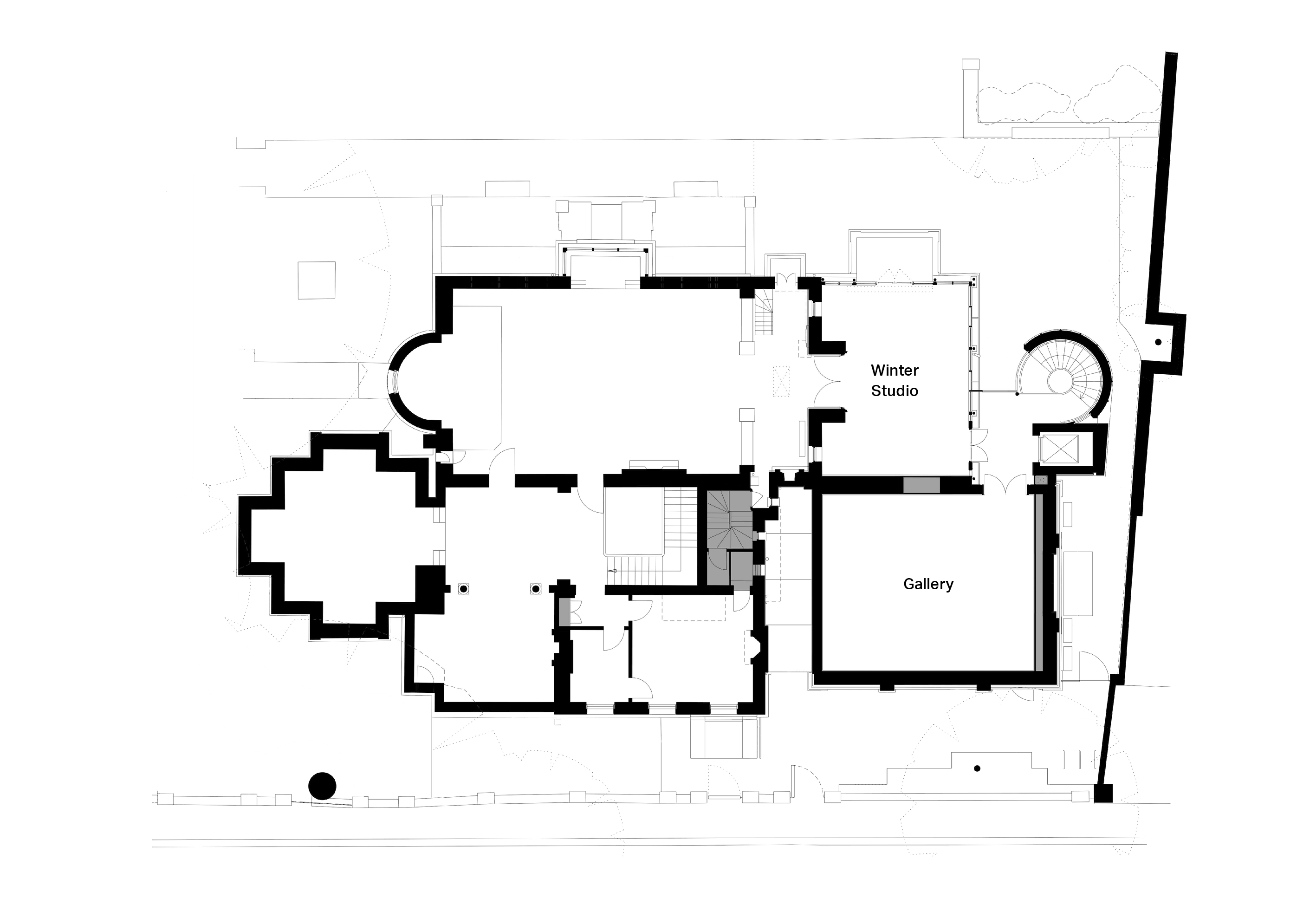

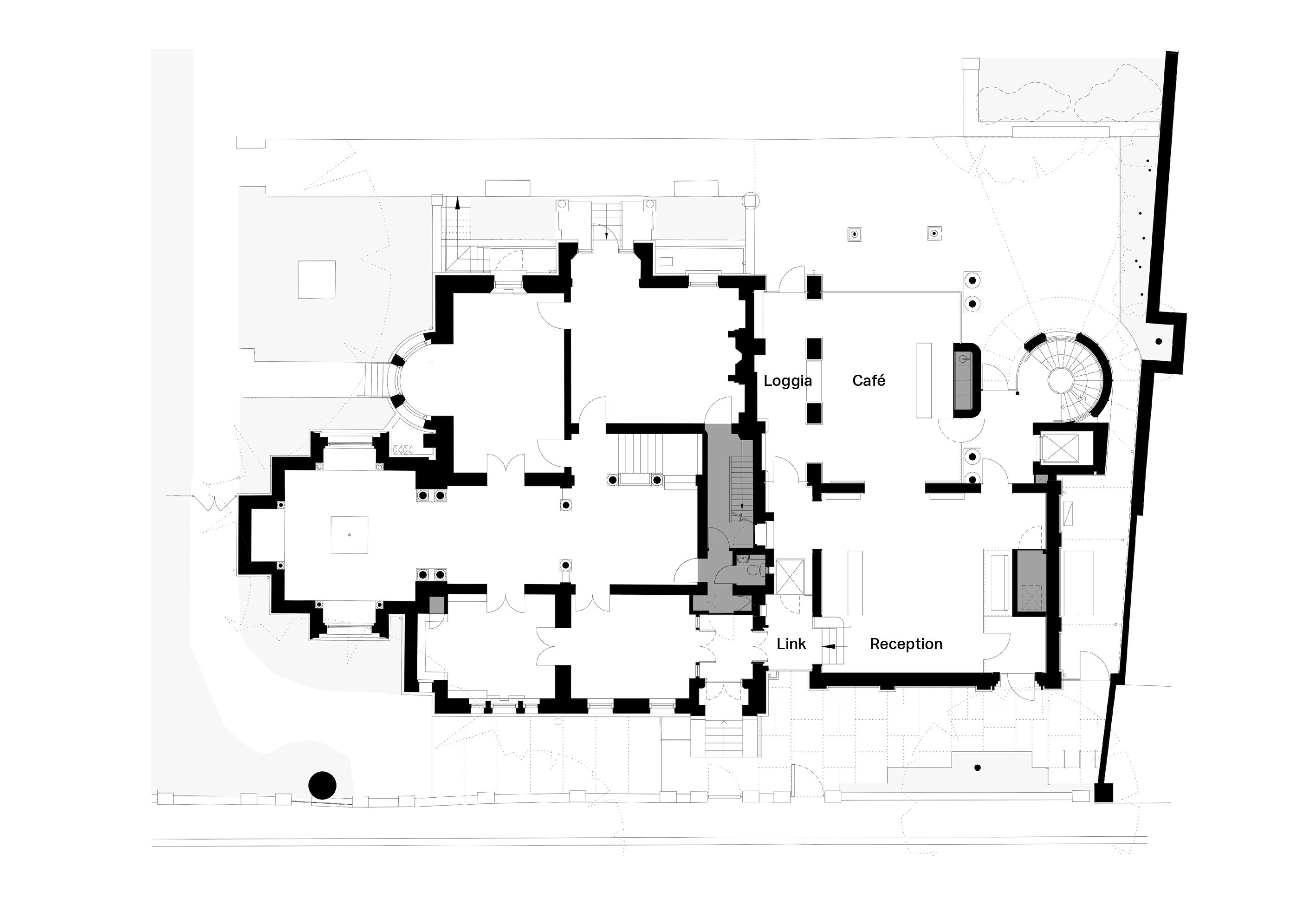

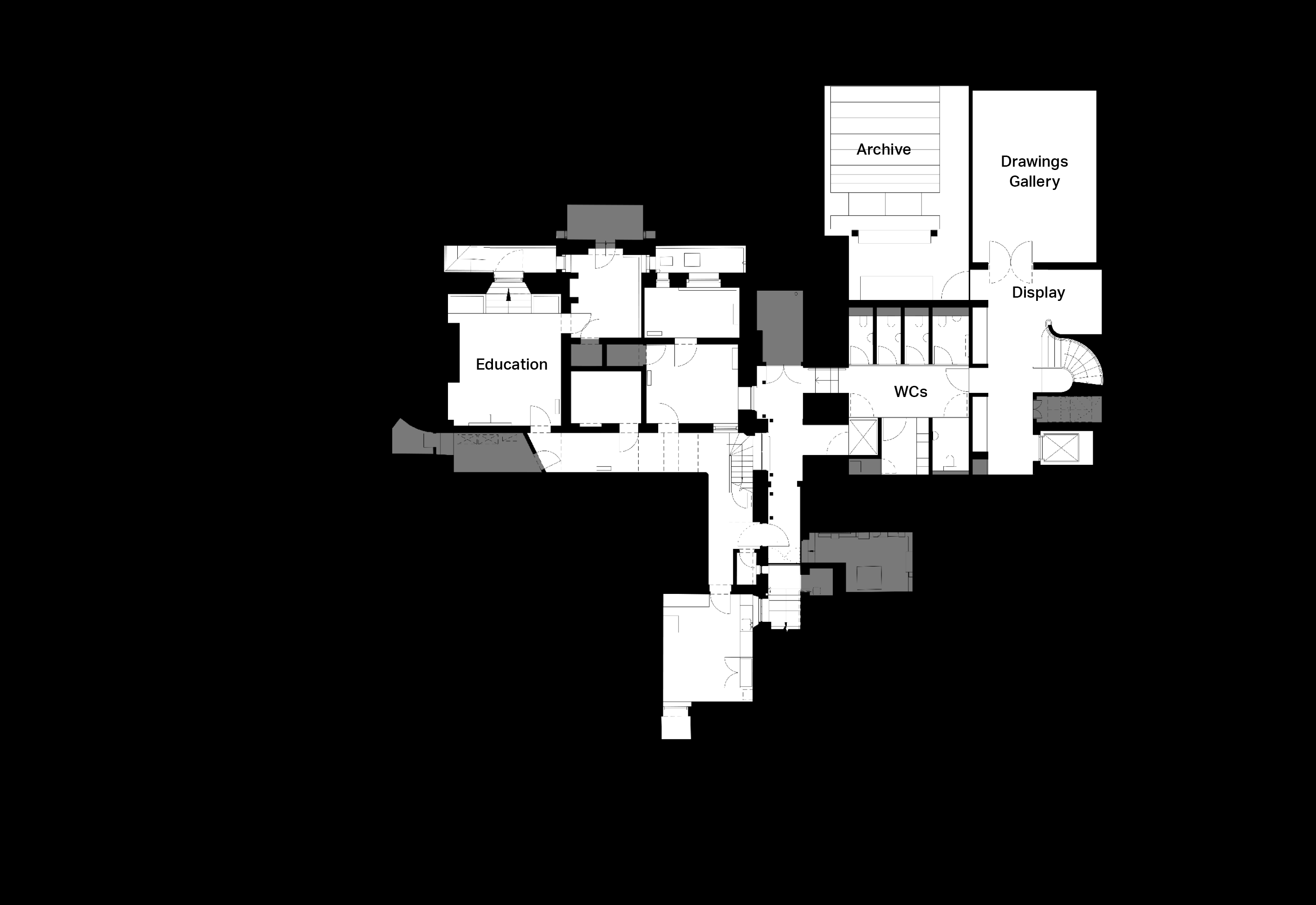

Two unsympathetic and underutilised additions built at the east end of the house in the twentieth century provided a possible solution. The idea that these spaces could be refurbished (removing in its entirety a particularly grim post-war piece of infill) and augmented to provide much needed new facilities, was the starting point for the project. In all, useable space, most of which is public, has grown by 43%. This comprises a new basement containing the public toilets, interpretation space a dedicated drawings gallery and the collections store. A rotunda at the extreme east end of the building connects this new basement via a lift and staircase to the two public floors above. The refurbished ground floor contains the visitor reception and orientation space with the fifties’ infill replaced by a café overlooking the large garden behind the house. Above, Leighton’s Winter Studio has been restored and reintegrated into the historic interiors with the temporary exhibition gallery now refurbished and the new museum office inserted above it.

These additional spaces have entirely changed how the museum functions, allowing far greater flexibility and increased capacity in the use of the building. But if practical and operational considerations were its main driver, the project has also prompted the reinvention of what Leighton House can be, enabling its relationship with the local community to be reimagined and its focus to be broadened into new areas.

The new wing, including the shop and café, is free to enter. As was hoped, local residents now see the museum as a place to meet friends and enjoy in a way that was not possible previously. The garden is also much better integrated with the house itself, visible through the floor-to-ceiling glazing of the café from the moment visitors first enter the building. Visible too are the neighbouring purpose-built studio-houses that border the garden. At its height, eleven studio-houses were in the immediate vicinity. All dating from the same period, additional interpretation has been introduced into the new wing enabling the museum to become the gateway into the discovery of the ‘Holland Park Circle’ and the phenomenon of the studio-house in the late nineteenth century.

Basement

Works by the Holland Park artists have been acquired for the permanent collections and form part of the material that is stored in the new collections store. Prior to the project, the reserve collections were split between four different locations around the museum, none of them fit for purpose. The largest component of the collection is the 700 sheets of Leighton’s preparatory studies. Drawing was of particular importance to his practice and the collection was put together as part of the original foundation of the museum following Leighton’s death. This collection prompted the creation of the dedicated new drawings gallery where selections will be exhibited as part of a programme that celebrates the art of drawing across all periods and cultures. In combination with the main temporary exhibition gallery, the museum is now able to develop varied and ambitious temporary exhibitions that both extend audiences and explore themes that relate back to the history of the house itself and what it represents.

The new wing deliberately expresses the extraordinary fusion of cultural influences present in the design of Leighton’s home. Principally this has been through the commissioning of the mural, Oneness, by Iranian artist Shahrzad Ghaffari for the new helical staircase. Conceived as a contemporary response to Leighton’s house and the Arab Hall in particular, the work speaks of the unity of art, architecture and craft and more widely, the possibility of greater cultural unity and understanding. A second commission through the Turquoise Mountain Foundation resulted in the suite of furniture for the reception and café. Made by displaced Syrian artisans now working in Amman, Jordan, the furniture is both contemporary while incorporating inlaid decoration that relates directly to a ‘sunburst’ motif inlaid into a Syrian chest front acquired by Leighton that is displayed within the staircase hall of the house.

The final transformation has been in the status of the historic house itself. No longer required to deliver the full range of museum activities, the house is now buffered and supported by the new wing. The emphasis can fully be on the presentation of the house, its interpretation and preservation, enabling the extraordinary interiors that Leighton created to become the new museum’s star exhibit.

The latest attraction set to draw crowds to Leighton House are three new exhibitions within the spaces created and reconfigured as part of the BDP project. Shahrzad Ghaffari, award-winning textile artist Nour Hage and Evelyn De Morgan, a pioneering artist from the Victorian era, are presented through new and rarely seen works which collectively explore themes of spirituality, symbolism and feminism. The new Tavolozza Drawings Gallery explores Evelyn De Morgan’s unique practice of making gold drawings and is the first display of these beautiful artworks made in brilliant gold pigment on dark grey woven paper, since 1896. ‘Journey to Oneness’ within the Verey Exhibition Gallery presents a curated selection of work by Shahrzad Ghaffari from the last fifteen years of her career, influenced by Persian poetry and artistic traditions and is themed around ideas of love, spirituality and identity.

To complete the display, ‘Kheit’ by British Lebanese textile artist Nour Hage showcases commissioned artwork based on Hage’s reinterpretation of visual symbolism from the Arab Hall and is displayed in the drawing room of the house.