← Archive home

Head of Sport, Dipesh Patel, talks about the future of stadium design and how it is increasingly focused on legacy and overlay.

Dipesh is an architect and urban designer and leads BDP Pattern, our sports and entertainment division.

He has over 30 years of experience in both the public and private sectors and has led projects in Europe, North and South America, Asia and the Middle East. Recent projects include the design of Everton FC Stadium, two stadia and masterplans for the FIFA World Cup 2022 in Doha, Qatar and eight venues for the Pan-American and Para-Pan-American Games in Lima, Peru, which include several multi-sports halls and outdoor sports facilities.

For readers who may be unfamiliar, can you provide some background on the formation of the company?

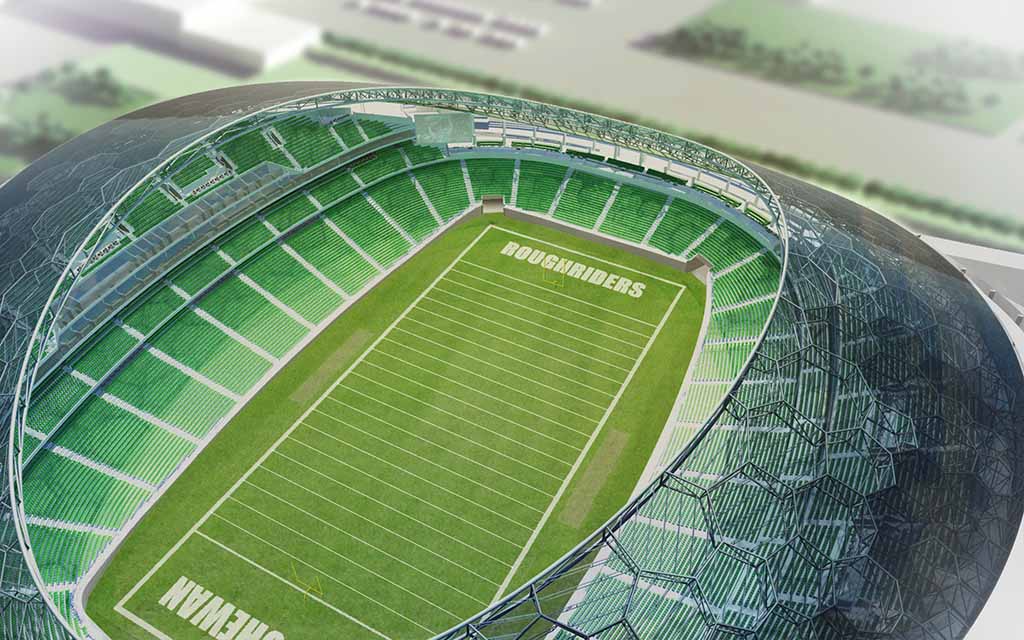

Pattern was founded in 2010 as a progressive studio working only in 3D with an emphasis on parametric, mathematical design and digital fabrication. We won our first five competitions, and our first built project in Al Ain is still regarded as a ground-breaking approach to stadia design. This led to projects in Qatar, Canada, China and the UK, making Pattern an established global sports practice.

In 2021 Pattern was acquired by BDP and now trades as BDP Pattern.

Personally, what is your background in the architecture sector and why was Pattern founded?

I studied architecture at Bath University. At the time, it was focused on integrated design between architects and engineers with our two professors Michael Brawne and Ted Happold alternating as Dean. This led me to join Arup Associates, who had a focus on integrated design. I began in the urban design studio under Michael Lowe. After 5 years, I took a sabbatical to study urban design at the University of Pennsylvania with a view to taking over from Michael. However, on my return, I was asked to lead the City of Manchester Stadium (The Etihad Stadium). This changed the course of my career and steered it into sports architecture. After Manchester, I worked on the Kensington Oval Cricket Ground for the 2007 Cricket World Cup.

By then, I had spent 17 years at Arup and I was reflecting on my career. I had always wanted to start a practice (I think every architect wonders about this at some point in their career) and the timing seemed right, so I formed Pattern in 2010.

How did Pattern’s acquisition by BDP come about and how has the deal supported the growth of each company?

Pattern’s portfolio and projects have attracted several major companies over the years. However, in our early years, we had not even considered mergers or acquisitions. By 2019, we had delivered many significant projects and wanted to have a greater global reach – all our competitors were much larger than us and had a significant global footprint.

For a medium-sized firm, delivering projects in multiple countries simultaneously is very difficult. We were in talks with a major global consultancy, but I was nervous about the cultural fit. However, a chance meeting at a conference in South America with a BDP Principal started a conversion about a merger. I found BDP to be an open-minded, thoughtful firm that cared about its people as much as it did about design. With BDP, we have been able to do this and we now have the huge benefits of a global footprint that will enable us to deliver major sports projects around the world.

How big a role does legacy play when designing a sports venue? How important was this when designing the Qatar 2022 stadiums?

I cannot claim any credit, but I did learn a lot from how Manchester City Council planned the 2002 Commonwealth Games. No venue was built without a strong use profile in legacy. All major events claim a great legacy idea, but very few are successful. Brazil has many unused and decaying venues and even our own Olympic stadium has taken a huge amount of money to create a compromised football venue.

In Qatar, we were designing to a wider brief for the World Cup. For Education City, we had the benefit of a major educational campus with the stadium as a central resource. This project was planned before Qatar secured the 2022 World Cup and was adapted to host World Cup matches.

At Ahmad Bin Ali stadium, we had the benefit of an established club with a stadium being rebuilt on the same site. From the outset, the focus was on legacy, both from the perspective of Al Rayyan SC and the local community. The site was, and is, much more than a stadium, it is a sports park for many sports and social events. Our masterplan focused on creating a community facility that suited the local culture of evening gatherings, walks and exercise. The Al Rayyan precinct was designed as a place for the community in the first instance and then ‘overlayed’ to ensure a World Cup match could be accommodated, without compromise.

“Brazil has many unused and decaying venues and even our own Olympic stadium has taken a huge amount of money to create a compromised football venue … The Al Rayyan precinct was designed as a place for the community in the first instance, and then ‘overlayed’ to ensure a World Cup match could be accommodated, without compromise.”

“I am confident that the few hundreds that attended prior to the new stadium will transform into capacity crowds.”

What specific legacy elements have been incorporated into the Qatar venues to ensure they don’t become ‘white elephants’ after the tournament?

Both the grounds we have delivered have uses that were in place prior to Qatar being awarded the World Cup; Al Rayyan SC is an established club and the new stadium replaces its outdated venue on the same site. At Education City, the stadium is a resource for all the students on the campus – much like an American university.

In addition, both stadia are broadly 50% permanent and 50% modular, allowing the capacity to be reduced for the legacy use to drive demand and generate an engaging atmosphere. Like our stadium in Al Ain, I am confident that the few hundreds that attended prior to the new stadium will transform into capacity crowds. The modular seating elements have a variety of legacy uses – they could be donated to grow football in less wealthy nations or used in community facilities across Qatar.

Are there any other examples of previous Pattern projects where legacy has played a key part in the design process?

The Hazza Bin Zayed (HBZ) stadium in Al Ain, Abu Dhabi is my proudest achievement. This city is equidistant from Dubai and Abu Dhabi. At the old stadium, matches achieved crowds in the region of 500, whilst the new stadium and enabling development has seen a change to capacity crowds for most matches.

HBZ stadium was designed with a clear goal – to become a new destination in the city of Al Ain, promoting healthy lifestyles and attracting a broader demographic. The wider masterplan includes a hotel, retail, commercial offices, a sports centre, museum, residential towers and villas. This has transformed match attendance from a short evening activity into a day out for families. The huge attendance at matches and the sustained footfall on non-match days across the development is a testament to the success of the legacy vision.

“ Most events are now becoming a day out with significant pre- and post-match entertainment including music, lectures and gaming.”

What emerging trends are you witnessing in the stadium design sector currently?

There is a clear upscaling of facilities. Even the general admission offer is greatly enhanced from a few decades ago, with better food and beverage offers, pay-as-you-go dining and higher quality concourses. In hospitality, there seems to be a trend away from boxes (suites) towards lounges. This offer is being stratified with a variety of options, from loge boxes to high-end dining. At our Everton FC project, we are going as far as introducing ‘show kitchens’ with celebrity chefs.

Technology is a major drive for change, bringing in greater fan engagement, better data collection, at-seat service and digital event involvement. Most events are now becoming a day out with significant pre- and post-match entertainment including music, lectures and gaming.

In a masterplan context stadia now offer a larger mix of facilities including retail, hotel and residential. One of our recent projects had a shopping mall embedded into the stadium. This variety helps revenue and daily footfall.

How big a role does sustainability play in the design of venues?

All our projects begin with an aim to maximise passive benefit. As periodic use buildings, stadia are very different to other projects and require a very different approach. Depending on location we are always balancing the requirements of the spectators with the health of the field or pitch. In hot climates the roof and facades are focused on passive cooling and shade, in cold climates wind protection and rain cover drive the passive design strategies.

The major resources for a stadium are water and power. The large roof areas are suited to power generation and, combined with battery storage, very well aligned to the periodic peak demand. At Everton Stadium we have no generators, only a large battery bank fed by rooftop photo-voltaic panels. Across most of our projects aerodynamic control is critical from passive cooling, minimising wind chill and good grass growth conditions. Established water-saving measures are now common and water harvesting is standard, but we are also researching larger-scale concepts to recycle water on site and improve water collection.

Social sustainability is an often-overlooked metric. As major community assets that drive social cohesion and community spirit, stadia can play a major role in building social capital and community pride.

At BDP, we are very focused on one-off events with a research programme to develop demountable and re-use solutions that avoid excessive expenditure and waste. We are very keen to open up world events to less-wealthy countries and improve sustainability.

“Social sustainability is an often-overlooked metric. As major community assets that drive social cohesion and community spirit, stadia can play a major role in building social capital and community pride.”

With the US also due to host the 2031 Rugby World Cup, is Pattern working on any rugby-specific venues in the country?

BDP has a major studio in Toronto and we are in discussion with a number of the clubs across the Atlantic. We also opened our New York studio in September 2022, marking the start of an exciting new chapter for our firm. We will release further details in the coming months.

NFL stadiums will mainly be used to host games – how can Pattern work with operators to help them navigate the challenges of staging a different sport?

Most major event authorities are now encouraging repurposing, reuse and modular. At BDP, we strongly support this much more sustainable and cost-effective approach, both to minimise environmental impact and to enable less wealthy nations to benefit from hosting major sporting events.

For the 2030 FIFA World Cup, BDP Pattern has the most current FIFA experience, and we would encourage an approach that is reversible and repeatable. In turn, this will allow the venues to host matches for 2030 and beyond as the game gains popularity in new territories, particularly the US and Canada.

More generally, what other projects are currently in progress for Pattern?

We are working with several UK football clubs to review their current facilities and set goals for future redevelopment. Internationally, we are working with clients in Japan, the Middle East, China and North America. All of these projects are currently under strict non-disclosure agreements, details will follow as they become public.

Everton’s new stadium is a major project – what opportunities and challenges has this presented?

The main challenges at Everton Stadium have been the waterfront location and the issues it creates around climate and single aspect entry. I am pleased that these have been overcome with detailed computer models to simulate the conditions and generate the solutions now employed in the design.

What excites me most about Everton Stadium is urban regeneration. This part of Liverpool has been in decay for decades. The very fine docks and surrounding warehouses are largely unused and closed to the public. It reminds me very much of when I first went to Eastlands in Manchester in 1998 when we started the City of Manchester Stadium (The Etihad). The area was one of the most disadvantaged in Europe with major social and infrastructure challenges. Today it is a thriving new part of Manchester with continuous development since the stadium was competed in 2002 for the Commonwealth Games.

The area that surrounds Bramley-Moore Dock is almost identical, with the key difference that it is a much more prominent part of the city. I hope and believe that the ripple event of Everton’s new home in that location will be transformational to the waterfront and city as a whole. It is estimated by CBRE that Everton stadium and associated development in North Liverpool will generate a £1.3bn boost to the economy, create tens of thousands of jobs and attract 1.4m visitors to the city. The stadium is not just a football ground; it is a once-in-a-generation project that will act as a catalyst for £650m of accelerated regeneration.

Everton’s new stadium will be the start or end point for a river-walk connecting the south of the city to the north as well creating new major public spaces for events on non-matchdays.

It will become a vital part of the city’s tourism offer. A new destination for anyone visiting Liverpool and for those cruise ships sailing past or the visuals on a postcards or through the images being beamed around the world, Everton’s new stadium will be the city of Liverpool’s ‘fourth grace’…

Is there anything else you’d like to add?

Just to note that as a practice, we recognise that the global pandemic has had a profound effect on society. Events were suspended for many months, social habits have changed and we are now in a cost of living crisis. With disposable income being strained, we are working to ensure venues support organisations so their attendance at sport and entertainment events remains strong. We understand that these events build social cohesion and provide a relief from the challenges of daily life. Looking toward the future, we understand the importance of team sport and know it has a huge social benefit which needs to be supported and funded for long term benefit of all our communities.