← Archive home

As the world grapples with defining socially progressive architecture in the 21st century, Isabelle Priest, Managing Editor at the RIBA Journal, examines its relevance and the need for renewed commitment to the common good.

It’s well known that BDP was established as a socially progressive practice. It was founded by George Grenfell-Baines as a multidisciplinary firm underpinned by the belief that the professions involved in designing buildings and, at the time, increasingly districts and places, should work together as one.

This was 1961. The Conservative Harold Macmillian was prime minister, succeeding Anthony Eden’s resignation following the Suez Crisis. Macmillian was the last UK PM born during the Victorian era and the last to have served in the First World War.

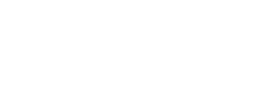

Grenfell-Baines was inspired by left-wing idealism. The practice flourished as construction did too – the first motorways, new towns, new universities, housing for all, designated shopping districts to serve burgeoning consumerism and improving standards of living. Unemployment was low and jobs were secure, with nationalised industries, health and a focus on education that had been rolled out by the Labour government in the late 1940s but continued under subsequent Conservative administrations. This period of improvement and progress began to define what individuals, families and communities could expect and hope for from their lives.

Grenfell-Baines died aged 95 in 2003. Twenty years after his death, this year’s big conversation is about ‘the socially progressive practice’. And the question of what constitutes a socially progressive design practice is as pertinent as ever, as well as less easily defined by the context around us. The phrase ‘fit for’ or ‘ready for’ the 21st century is still so often used that it has become a trope to mean ‘new’ or ‘of the moment’, and rarely questioned. For me, 2018 was the year when I felt we had collectively left the 20th century behind. Many of its heroes were no longer with us. The welfare state – healthcare, education, social security – had become no longer so dependable. The unwritten social contract between generations and the idea that the next would be more prosperous than the last felt broken. The 20th century’s political systems seemed to be unravelling too – in the US with Trump generally and the threat to NATO, the EU crises through Greece then more so via Brexit. In the UK, Nicola Sturgeon looked like Britain’s most credible leader and the possibility of Scotland leaving the union more a case of when, not if.

In the design of the built environment, we had seen the proliferation of projects didn’t meet the needs of most people. School building programmes cancelled, scant renewal among hospital and healthcare buildings, and instead there was a rich seam of super luxe houses that architecture practices were prohibited from publicising.

That is why, a couple of years earlier at RIBA Journal, we launched the MacEwen Award to celebrate architecture for the common good. We didn’t know what it might uncover, but it was positioned to counter this prevailing direction whereby architecture appeared to be losing its social idealism. BDP has partnered with RIBA Journal on the MacEwen Awards since its inception. This year’s winner is the revival of Jubilee Pool in Penzance by Scott Whitby Studio with a new café, community space and geothermally heated section of the pool so it can be a year-round destination. Now in its eighth year, with each cohort of entries, shortlisted projects and winners, we are starting to see what ‘common good’ in the 21st century means; environmentally sustainable, socially inclusive and caring, conceived and brought about communally. Projects often have reuse as a central feature, as well as rescue – be it of a building, place or community.

These are features that during the pandemic gained a lease of life and mass appeal. In the space of a few short years, the idea, for example, of designing fully glazed buildings has almost become irresponsible. Politics too appeared to have softened with a more established acceptance that everyone should be cared for during tough times, and that all workers deserved fair pay, particularly lorry drivers, supermarket staff as well as nationalised and unionised ones. The pandemic appeared to be consolidating existing low-profile shifts in where people work, what they do and what they want from their lives.

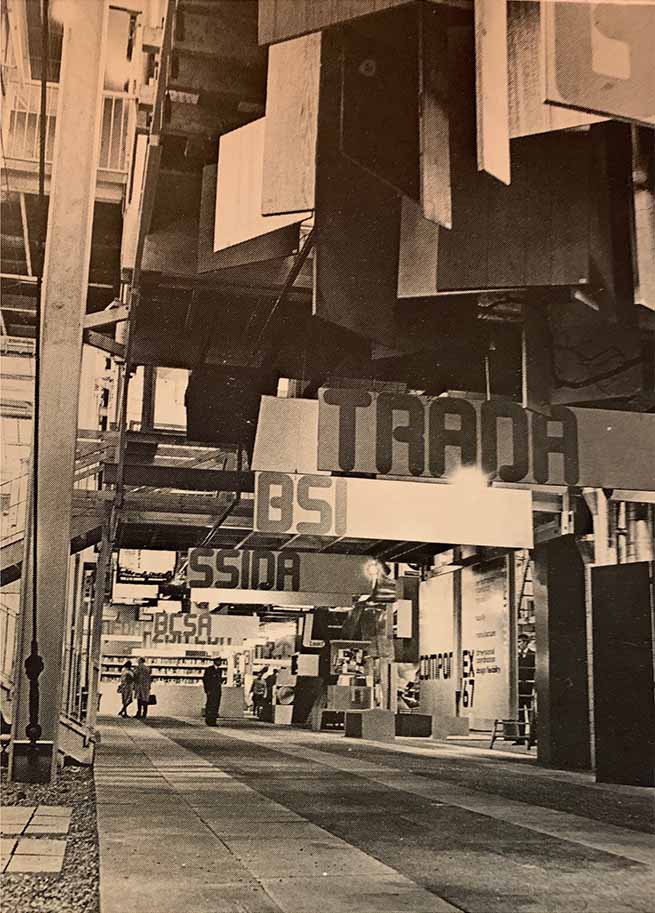

During the twentieth century, crises became sources of great social change. The post-war consensus that emerged following the Second World War was an economic and social equilibrium that brought about peace and prosperity. Likewise, similar renewal and progress followed the First World War – liberal reforms and enfranchisement. In architecture, it manifested as Homes for Heroes, but also in health, hygiene and wellbeing-focused architecture across the western world. Berthold Lubetkin and the Tecton’s Finsbury Health Centre built between 1935 and 1938 is a prime example, although it has now seen better days. Vast swathes of society were no longer willing to endure the existing social order. The houses Le Corbusier designed in the 1920s and 1930s that become a model for so much architecture during the 20th century were designed with servant spaces that within only a few years of completion were mostly unoccupied as women left domestic service.

The Nightingale Hospitals was BDP’s major contribution during the pandemic. The World Health Organisation puts the current reported death toll from the Covid-19 pandemic globally as 6.9 million. However, the current inflation and cost of living crisis is in danger of smothering the conversations and progress that had gained momentum during the pandemic – fair pay, looking after the planet, public space, social good – as well as harden attitudes as they did following the financial crisis in 2008. Perhaps the biggest break with the 20th century is that in the 21st century responses to crises have been short-term or reactionary, and haven’t led to sustained positive progress.

A project being socially worthy doesn’t necessarily make it good design, as BDP’s head of marketing in the North region Alex Howe says:

“There are lots of socially worthy endeavours trading out of terrible buildings. The trick for us is to demonstrate that good design can elevate a socially worthy activity into a wonderful, life enhancing experience for the people who use it, work in it, or pass by it in the street. For example, in hospitals this can include break out spaces, daylight, views, space for families and healthcare professionals and good landscaping.”

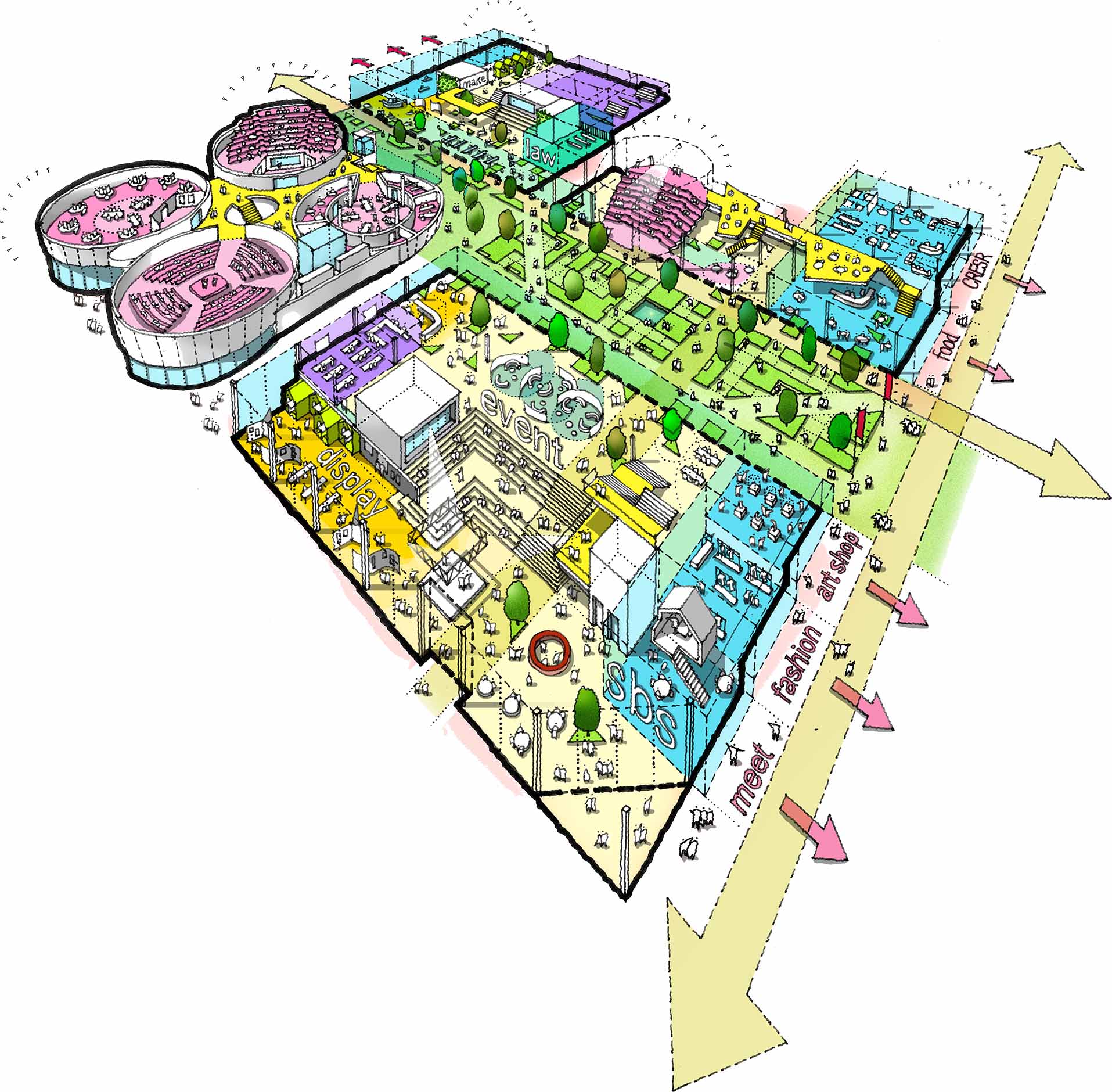

The brand new Newmains & St Brigid’s Community Hub in North Lanarkshire, is also more than just a primary school, but a hub that provides for 600 pupils and members of the community, via shared and overlapping spaces, including for a nursery, and mother and baby groups. Likewise, in Gouda the Netherlands, the upcoming Westergouwe Community Centre is a truly mixed-use scheme that is designed to connect the social structure and wellbeing of a neighbourhood. It will provide a primary school for 1,200 children with additional daycare services, as well as a modern sports hall, a community programme and 40 affordable apartments. Human Space in Toronto is an arm of BDP that is focused on accessibility and inclusivity. Its Heritage for All project for the government is about making Canada’s eminent buildings accessible

Social value is integrated in what the practice does via its projects, but also through its internal and collaborative programmes. BDP’s network of offices across the UK and globally means that the practice has a greater potential for outreach and inclusion. For example, since the practice’s apprenticeship initiative 10 years ago, 95% of these apprentices are still working for the company. PPN14/15 and PPN06/20 have seen shifts in public procurement that have become more than a requirement simply for bids, and now they are making their way into the private sector too, shifting corporate social responsibility into inherent social value. The unique NEC4 Alliance contract that BDP has with Sheffield Hallam University, CBRE and BAM creates jobs, apprenticeships and cross-company three-week placements every January. Meanwhile, this winter the practice’s ‘Giving isn’t Seasonal’ campaign initiated a food bank collection across all UK offices.

These are steps that need replicating across professions and industries. Looking back to the start of BDP to look forward, let’s not allow this opportunity for a post-pandemic consensus to slip away.

Isabelle Priest is a journalist and writer on architecture, and managing editor at the RIBA Journal. Her essay ‘Le Corbusier’s artist houses 1922–1935: Machines for more than artists to live in’ is in the next edition of Open Arts Journal.

A project being socially worthy doesn’t necessarily make it good design, as BDP’s head of marketing in the North region Alex Howe says:

“There are lots of socially worthy endeavours trading out of terrible buildings. The trick for us is to demonstrate that good design can elevate a socially worthy activity into a wonderful, life enhancing experience for the people who use it, work in it, or pass by it in the street. For example, in hospitals this can include break out spaces, daylight, views, space for families and healthcare professionals and good landscaping.”