← Archive home

Iris Dunbar was the first qualified interior designer employed by BDP in 1972. Here she explains how she and her three collaborators came to conceive BDP’s interior design unit whilst sharing her knowledge from 50 years of working in the profession.

Hi Iris. Tell us a bit about yourself and how you came to be one of BDP’s first interior designers.

Well, like much of the design inspiration in the country, it was during the Festival of Britain in the 1950s when the interior design discipline developed into something that veered towards commercial offices and away from what we called interior decoration or designing homes. Studying the 20th Century history of Design helped to spark a life long interest in art and design.

I went on to complete an interior design degree at the well-established Duncan of Jordanstone College of Art, in Dundee. Funnily enough, it was an architect who decided that interior design should be taught within the architecture school. Prior to that it was a separate furniture or soft furnishings design course, so I guess the blurring of architecture and interior design started just as I entered my education in the profession.

Yes, it was an art school but my course focused more on the relationship between sculpture and space so it felt like a more artistic curriculum but the subtle influence of architecture on what we were learning was clear to me.

And the concepts we learned about such as space, light and colour remain unchanged today. Even when people talk about sustainability, I recognise learnings from my degree about ‘appropriateness’. As designers, our job is to always design in an appropriate manner. It’s just that now that is about, first and foremost, looking after our planet.

But we must always merge being appropriate with creativity. That comes with an ability to analyse and provide solutions within the constraints of a building or a project. And I think that was what was so appealing about working as an interior designer within BDP. It was the ability to understand a whole project, its limitations and constraints and then to let everything go to allow freedom of thought to find something that is unexpected. We were able to sit at the top of the hill and take our feet off the pedals. That’s why designers are there: to open the book a bit more and not just accept what a building might present on face value.

It is claimed that BDP was the first architecture practice to integrate interior design in 1974. Can you explain how that came to happen?

I think it’s true. I recall that other architects like Basil Spence were hiring a cohort of furniture designers to work with the architects on the built-in furniture within their buildings. Understanding the that the interior should be integrated into the building design was very important.

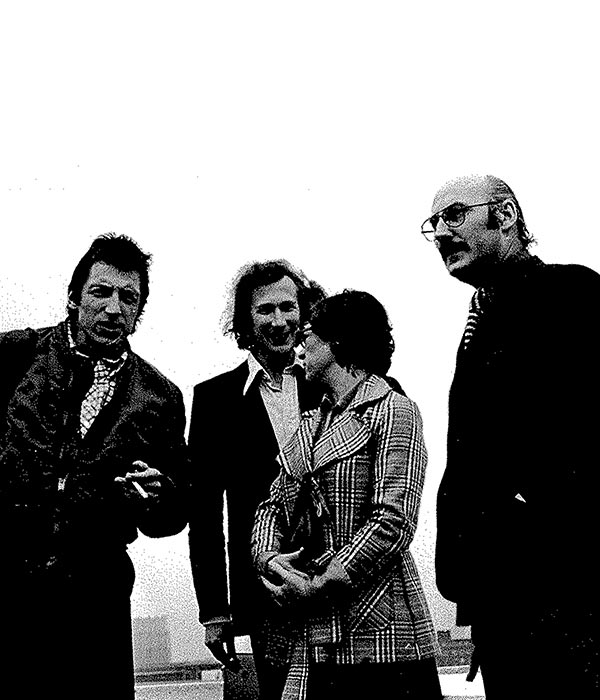

I came straight out of art school and was interviewed by Bill Jack in 1972. He was from Aberdeen so there was a definite Scottish connection. He understood the opportunity and also how good the course was at Dundee art school.

Rodney Cooper joined me in 1973. He also came from Basil Spence’s practice and had a good grasp of furniture design but also of architecture. It was he who changed the approach of BDP. It was the conversations he would have in the lunch room with architects that enabled him to operate so effectively and be seen as more than a furniture designer. He was one of these personalities that really championed good design.

John Barker and John Pinder joined soon after and together we would discuss how we designed commercial buildings from the inside out. We decided that design was more than just furniture. In fact, we used to tell the architects that if you turn the building upside down, everything that falls out is interior decoration. The rest is interior design! That really got the cogs turning!

Interior design has always been about tapping into the senses. Everywhere you stand or sit affects what you hear, see, smell or feel and what we always wanted to do was to tap in to that! It really set the basis for everything we did.

You could argue that workspace design’s golden years were in the 70s. What was it like designing office spaces in that period?

It was the beginning of the age of the Herman Miller action office. That change from rows of desks to understanding how companies actual work was prominent. It was fascinating to be a part of that movement. Clients would be surprised at the questions we would ask and we had to explain that we really needed to know about their businesses to design the best spaces. To be able to plan effectively, we had to hear, understand and see what was going on.

This was the real beginning of breaking up spaces and opening up offices. You had to make sure each grouping for teams were in the right space and create open spaces next to busy spaces. Using storage and planting to create these blocks or areas that supported collaboration or indeed privacy.

We started to see people would meet at filing cabinets with their elbows on the top, rather than in meeting rooms. We were creating the water cooler moments. It was natural and it was exciting.

How did you conduct the research into your clients and businesses?

There was an awful lot of research involved. We would survey business owners, staff members, cleaners and everyone in between. It’s a practice that we still see today. I think, with technology, the method of collecting data has changed but the data sets are more or less the same. Does the design work to bring people together? Does everyone like it? Is it properly occupied and utilised? Does it increase efficiency and enhance feelings of wellbeing?

To get a space that works. You really need to ask all these questions but I firmly believe that as designers we have a responsibility to direct the design into something that looks and feels great. For example, back in the 70s, we would have to convince clients to adopt a contract with gardening companies to install and maintain planting. Of course, we now refer to biophilic design but the benefits of greener offices were, and still are, very clear.

And its things like this that then go on to affect the lighting strategy in a building. For example, is the daylight then sufficient to support the planting as well as the people doing their jobs? Design is an unstoppable process. Every intervention, every project brings a new challenge.

What would you say your favourite design trend is from the last 50 years?

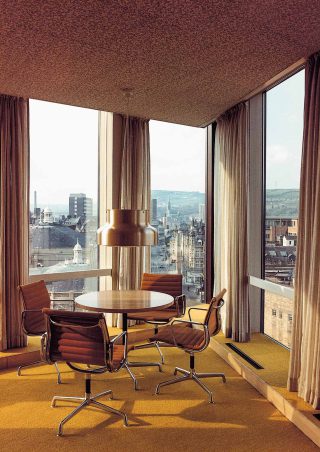

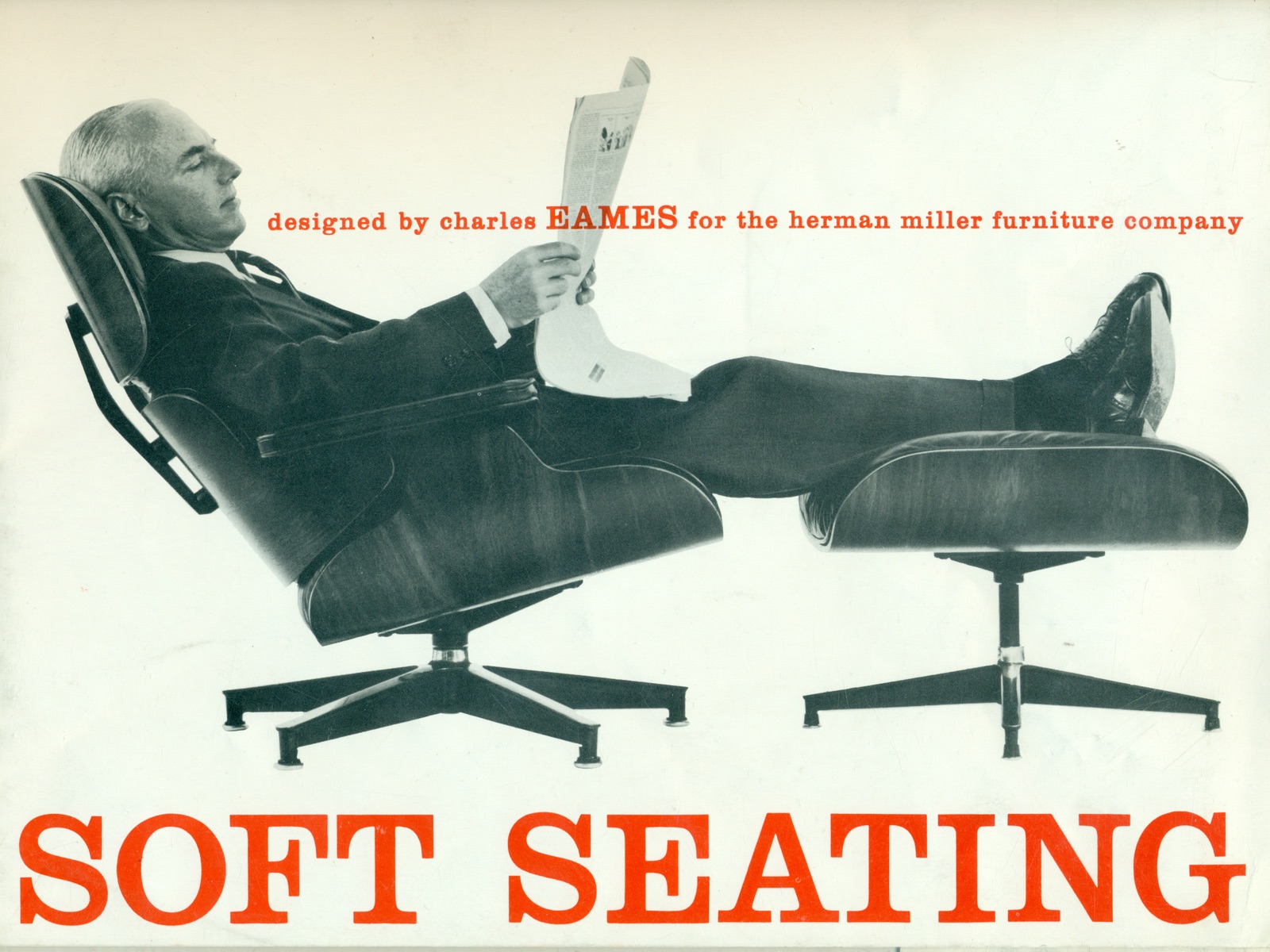

I like a classic style, I’m really into furniture of value that brings longevity. And some really well-designed pieces still have mileage. Some designs from the 60s and 70s still work today. We didn’t know that they were classic at the time but look at the Eames chairs; still widely used today and as contemporary as ever.

But overall, design for me has always needed to have a balance of light, colour and texture – I despise anything that could be considered bland. Its not so much a style that I favour but I like things that have function and I like to see designs that support those functions, designs that really work.

Its more a case of seeing things that are considerate to the building itself. Our job is to pull out the character of the place and integrate it into the actions of the people who use it and crucially to make sure they embrace it. If you can balance place, art and considerate design with solid, timeless furniture, you’re on to a winner!

Why do you think BDP’s approach to Interior Design has worked for 50 years?

There has always been a breadth of thinking at BDP. Its mission statement of socially progressive design to create places for people enabled it to find projects to support grand ideas. The scale of the company meant that we were given opportunities to express ourselves and create some amazing designs. You only need to look at projects like the Halifax Building Society and the Logica offices in London’s Newman Street to see that we were using free form design, integration of art and extravagant graphical wayfinding to create something entirely different.

I think about other friends who worked in the industry, and they didn’t have the same opportunities as I did. At BDP we were always encouraged to think more about the project and how the building came together as a whole. We had big remits to cover and every single piece of design was considered to help the building work for everyone. It came down to the smallest details. We thought of everything from the feeling of the reception areas down to the colour of the pencil trays!

Interior Design professionals have got to recognise that our job is at the end of the line. Which is why we need to ask the most questions. It feels personal. If you’re designing a space that fits 300 people, its down to us to make sure that the space works for every single one of them. I think that’s why BDP has been so successful over the years, its always listened to its clients and to people and translated that into beautiful, functional places.

Of course, understanding the outside of the building is so vital and then interpreting that into how people travel inside is a mark of BDP’s projects over the years. If you understand the architecture, the engineering and the building services, you can design a better place. Its as simple as that.

Moreover, you’re in the company of those you trust. There is an unwritten synergy between all these professions and I think BDP is quite unique in that sense, it feels like a place where people trust each other and crucially, the design process. The structure of the company can only be an advantage moving forward and I believe that interior designers will always have an important seat at the table.

Iris Dunbar is the former President of The British Institute of Interior Design, the International Federation of Interior Designers and founder of The Interior Design School. She is a pioneer of Interior Design in its modern form and has combined teaching and practice over her career informing her strongly-held view that Interior Design should be taught within a professional framework.